Q&A with Jael Richardson, author of Gutter Child

by Laure Baudot

Photo of Jael Richardson by Simon Remark.

Jael Richardson’s first novel, Gutter Child was published in January 2021, and is already on the Toronto Star’s bestseller list. Richardson, the founding director of the Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD), is also the author of The Stone Thrower, a memoir about her father, Chuck Ealey, a former CFL quarterback, and a children’s book based on the memoir. She has been a supporter of the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction for a number of years.

Gutter Child tells the story of Elimina, who lives in a dystopic world divided into a privileged Mainland and a policed area called Gutter. Elimina is one of 100 children chosen to be part of a social experiment where a Gutter child is raised on the Mainland. But when her mother dies, Elimina is forced to enter a social system where Gutter children, including teenagers Rowan, David, and Violet, face various injustices.

A plot-heavy page turner as well as a work of beautifully crafted social criticism, Richardson’s book fits solidly into a body of dystopic work by BIPOC authors, including Colson Whitehead (Zone One, The Intuitionist) and Rivers Solomon (An Unkindness of Ghosts). Told through a race-based lens, Gutter Child also speaks to experiences of class and gender.

The novel’s critique of racism, which it links with colonialism, is a familiar one. Explorers arrive to an inhabited body of land—the Mainland—and displace, kill, and enslave its inhabitants, all in the name of a complex web of racist, nationalist, and capitalist ideologies.

Empowerment in Gutter Child emerges in various forms: in community building, social action, and text. Poetry, in particular, provides Elimina and her companions history, connection, and comfort.

LB: Congratulations on your recent publication. There is a long-standing relationship between the dystopic genre and social criticism. Can you tell me about your choice of genre?

JR: I had just finished writing a memoir and I was steeped in fact and truth. I wanted to be free of that, to move into a space where accuracy was up to me. Dystopia not only allows you that kind of freedom to move beyond boundaries and borders but also allows you to criticize the world. I was really influenced by Toni Morrison’s Sula, I loved the way that book created a space where you could think about the Black experience without being so rooted to all the things that people were familiar with. The genre provides a place to pull together communities that maybe are separated by borders and address some of the politics that unite us.

LB: In Gutter Child, communities and families are fractured by a racist system. In their wake, new communities emerge, communities based on shared experiences and strategies of emancipation. Talking about his friends at Livingstone Academy, the character of David says, “Being so far away from family for so long…I don’t know…it felt like we made a family of our own.” Can you talk about how you see these new communities? Is there a gendered aspect to them?

JR: It’s important for me to be clear that nowhere in Gutter Child are people referred to as being Black. They’re Gutter folks and most importantly they’re Sossi people, they’re joined by being a part of this land that they lived on, that was theirs.

The Stone Thrower children's book was inspired by her memoir of her father. Here Jael signs a copy at an event for school children. Photo by Herman Custodio.

LB: I noticed that [choice], and I wondered if I should talk about your book in terms of the Black experience, and obviously I can’t not talk about it, given who you are and your past writings and your position at FOLD…. Could you expand on your decision?

JR: Tactically the book is based on the Black experience but Elimina isn’t ever described as Black. The word Black is tricky. It’s a word we’ve re-appropriated and I’m very proud to use it, but on the other hand, it was given to us with negative associations. Ian Williams [recently posted that] he looked up in the thesaurus other words for threatening, and “black” came up. I wanted to not use that [word] in the book. Also, it’s not used everywhere in the world in the same way when it comes to Black folks, for lack of a better word.

I chose the word Gutter because I wanted that same connection to negativity—no one’s going to think of the word Gutter as positive, and no one at the time that they were naming people Black, really thought of [the word Black] as positive. So Gutter and Black have a connection. I wanted to use Gutter in the book to point to that and I didn’t want to use the word Black. I wanted it to be accurate, I wanted to describe their skin colour, I wanted to describe their hair, and of course when you do those things, that connotation, this plus this, equals Black for us. But the term or the word isn’t quite accurate. That’s the decision making I did around that book.

LB: Circling back to my question about new communities in your book. Is there a gendered aspect to them?

JR: Community was what I saw as the thread that carried everyone through. Whether they were moving toward the Gutter or moving out of the Gutter, community became a very important part of surviving, and there is a gendered aspect to it. One of the reasons I wrote this book was because I was thinking about my father and the way he was able to move out of poverty and debt, and I was thinking about the women in his community who had a more difficult time doing that because of way men move through the world. Women have to form a particular community to emancipate themselves and approach freedom because our freedom is different from the freedom of men. I also think it’s a commentary on class. Class-based community is important because to fight for freedom when you are poor is different from fighting for freedom when you have more means.

LB: Your characters use various strategies of empowerment, including community building, public protest, and, of course, text. When she first encounters a book of poetry from the Gutter, Elimina refers to the poems as “whirling dreams that shatter darkness.” Is there a link between literature and surviving trauma?

JR: Literature has played an important role in helping me see myself and the world more clearly. There’s something about reading someone else’s words that match what you’re thinking that helps you say wait, I’m not alone and this is something worth talking about. The poems in [Gutter Child] have an ability to help all of [the Gutter characters] understand that even with their differences, these poems speak to a common experience, a common way of struggling in the world.

Collectiveness is what helps Elimina understand her place and what she needs to do eventually, and it’s what joins [the Gutter characters] together and helps them put the things that are different aside to meditate on [the poems.]

LB: Can you talk to me a bit more about the connection between text and social action?

JR: One of the things that’s unique about poetry is that it’s from a generation before, so it becomes a way of passing down and sharing more widely the things that are going on. That’s an important part of activism. Text allows us to remember. Recently people have quoted James Baldwin and Langston Hughes to show that we’ve been talking about this for many generations and it’s that text that elevates the activism. Because it’s not like, “Oh this is kind of bad.” No, it’s bad and it’s been bad for a long time.

LB: You’ve touched on this. Men and women in Gutter Child experience life, and racism, in very gender-specific ways. With Rowan, who is encouraged by the Mainlanders to box but only to win within proscribed limits, you appear to explore racism’s devastating impact on Black men. Can you talk about how race and masculinity intersect in your book?

JR: The difference between how racism and systemic racism affect men and women is one of my greatest fascinations. You see it with David and his hiring, and the way men and women are hired, with different value systems. One of the challenges is that Black men in particular are valued for their strength and there’s an inability [for them] to show weakness. There’s not a lot of room for them to be their full selves, to be complicated. There’s a trauma that comes from that. Those Black men will understand how they’re valued, and sometimes they can fit into that mould. I would say that my father fit very nicely into that mould. He was very physically successful and was so celebrated for that, but if he tried to step out of that box, it was very difficult for him, and that’s what I wanted to speak to with [the character of] Rowan in particular.

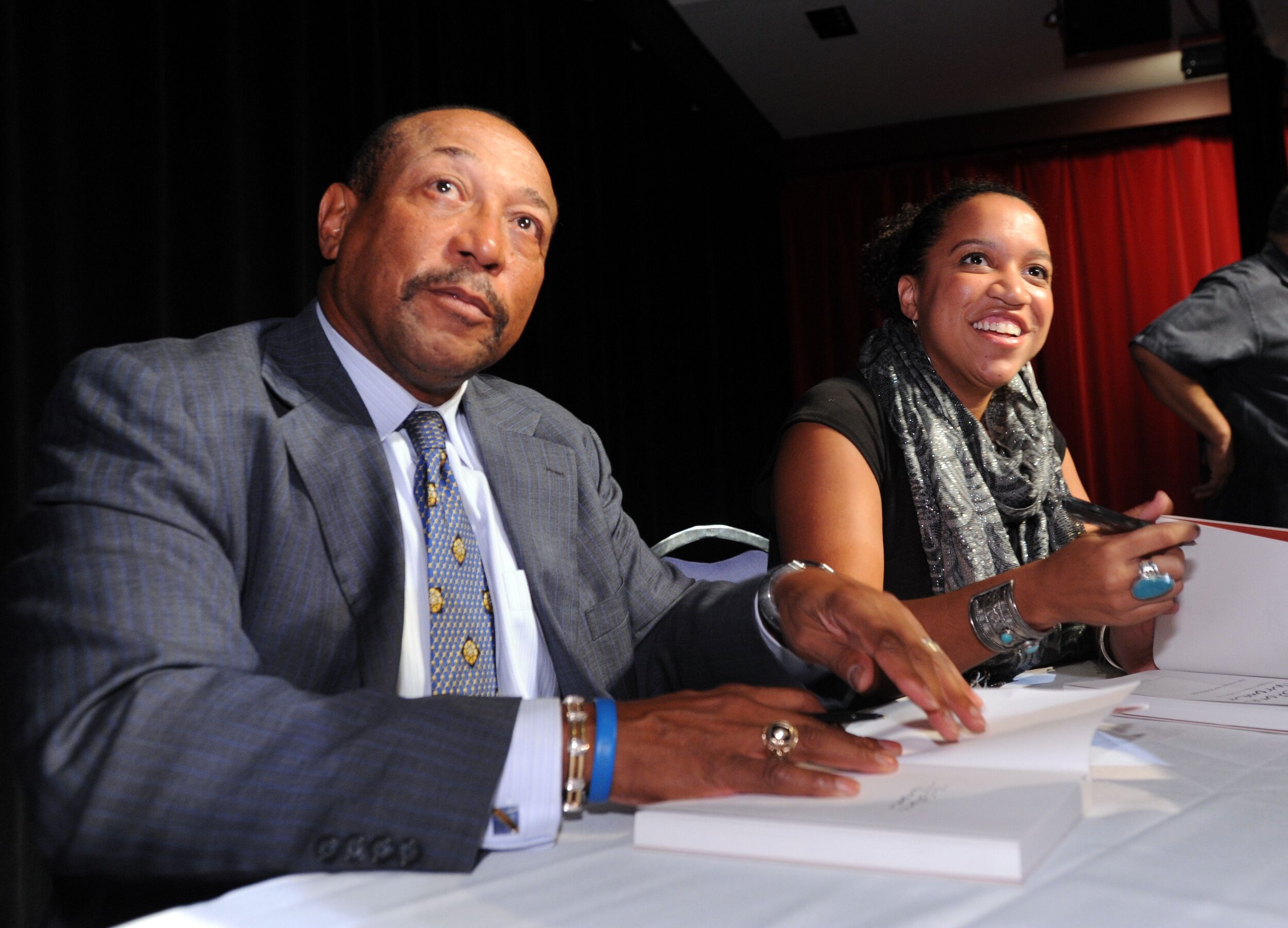

Jael and her father, football star Chuck Ealey, signing copies of Jael's memoir, The Stone Thrower. Photo courtesy of Jael Richardson.

LB: What about your female Gutter characters? They are victims of race-based sexual violence, but they are also sometimes disempowered by other Gutter children. Can you speak about the experience of being Black and female as you’ve portrayed it in Gutter Child?

JR: One of the most difficult parts of the book was how to represent the female characters of the story, because I wanted to be full and thoughtful but I also feel that women of colour have it particularly hard. They have the challenges of being racialized but they also have the challenge of being gendered. In both ways they face the challenge of being overlooked and oppressed while also carrying the responsibility of trying to fix that, for themselves, and for the wider world.

At the end of the day, the female and male characters share community, and what they’re suffering they’re suffering together. The women are in the hardest position, but they also know that they’re not alone, that what they’re struggling with is also a symptom of the system.

LB: You’ve partially answered my next question. When Elimina gets pregnant by Rowan, I didn’t get the sense that she’s enraged at him, and I kept waiting for her to explode, because her situation, which is already dire, gets worse. I wondered why she wasn’t angrier.

JR: Those two moments with Elimina and Rowan sat on me the longest, because they were the scenes of most overt violence. What I have to remember about that scene with Elimina and Rowan is that Elimina is about fifteen, and her desperation for closeness means that everything negative that comes along with that was a result of that desperate need. When you strip away all the relationships that Elimina has ever known her full life, and then you offer a small glimpse of closeness, I think you take it, even when it hurts. At that moment when she could get angry at Rowan, I think a bigger concern is that he’s gone, that she doesn’t have anyone [left] except maybe Ida.

LB: Motherhood is a central theme. There are biological mothers and women, like Ida, who appear to act as surrogate mothers to Elimina. What are some of the ideas related to motherhood that you’re exploring?

JR: Motherhood is complicated in the book and also in my life. In my own life I’ve had my son, and I’ve also had adopted children and foster kids. I was working on the book when I was fostering two teenagers, so [the question came up] about what it looks like to be a mother, what your role is as a mother regardless of how [children] come into your life or regardless of whether they come from your body.

In the Black community in particular, I wanted to explore some things through the Gutter children: what happens when we’re torn from our biological families, when we’re returned to our family and community, what happens when you are left without family and community or when you are left without biological family and find community.

There are things that the Black community does really well, that we don’t often pay attention to. We look at absentee fathers and single mothers and make these very broad statements, but most people I know from single parent homes in the Black community will also say that they have fathers and uncles and aunties that fill in for whatever parent is not around and that even when you have two parents there are often other parents that come alongside you. I was trying to call attention to that, that in the Black community, we actually take care of each other pretty well. There’s a way we can heal by being together. And motherhood is a key way that [this healing] is done—through the female characters in particular.

LB: The ending is untidy, and the reader is left to draw their own conclusions regarding’s Elimina’s future. Without giving too much away, can you talk about the decision that went into the ending?

JR: I’ll say that up until the last minute there was an epilogue. Every time I turned the page I thought ugh, I feel like I’m reading a whole new novel. I started thinking, what happens if we don’t have an epilogue? I just took it off, and I loved it. I felt like I was leaving the reader to decide a whole bunch of things.

Also, when you’re writing a dystopia you’re left with three choices of how to end. You can be optimistic, you can be pessimistic and create a doomsday the world is terrible vibe, or you can be realistic. I chose realistic. I feel comfortable with where it ends because I think it’s true to the themes of the book.

Jael launched the Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) in 2016. It's the first literary festival devoted to celebrating underrepresented authors and storytellers. Photo by Herman Custodio.

LB: You’re not only a writer, you’re the founder and executive director of FOLD. Can you say a few words about BIPOC writers and the Canadian literary scene? Has the market improved for BIPOC writers?

JR: When we started FOLD the issue we thought we were addressing was a lack of representation in Canadian literature. What’s become a more obvious [problem] is the systemic racism in publishing. For example, certain kinds of stories by BIPOC writers are likely to be published, but the avenue for romance writers or sci-fi writers or books outside the box was more difficult. There wasn’t really a willingness to take risks [with romance and sci-fi], or to discover new readership.

Another thing is [we have] an industry that’s largely white, largely female—and male at the very top—that isn’t providing the support for those writers. I was talking with Lawrence Hill about the fact that he’s published all these books about the Black experience but he’s never had a Black editor. All that to say, I think things are moving in the right direction but it’s slow and it’s going to be continuously slow because at almost every step there’s a measure of convincing that has to happen.

LB: Who are your literary influences?

JR: The three I hold in high regard for their craft are David Chariandy, Katherena Vermette, and Heather O’Neill. One of the reasons I struggled with Gutter Child is that I find it sounds like none of their books. Writing my first novel, I had to come to terms with [the fact that] I write the way I write. It’s certainly been influenced and shaped by what I’ve read from those three authors and others—Andre Alexis is another one—but I can only write like me.

The Festival of Literary Diversity has become one of the most popular and successful literary festivals in Canada. Photo by Herman Custodio.

LB: You’re very busy. Do you have a writing routine?

JR: This book took eight years to write. I sort of wrote from my heart initially. I didn’t think about the structure, or how it was going to end. Once you get to those points, where you have to think about the structure, you have to think about the end, it changes everything. It took me a long time because I was figuring it out. [Working on] my next book, I’m obsessed with being more efficient with my time and my writing.

I’m not somebody who can easily write every day. I’ll take a week where instead of working I’ll write in the morning and work in the afternoon. I’ll also take weekends where I just say, look, family, I don’t know who you are, for two days. I just lock myself away and write and write and write.

LB: Do you have any new projects in the works?

JR: I’m working on a sequel to Gutter Child. What I’m excited about is I don’t think anyone will see it coming, where it begins, what it’s about, how it unravels.

The minute I’m done a manuscript, I start writing the next one. [What I usually experience is] a new idea sitting on the surface but I can’t see anything of it. As soon as I send the other manuscript in, the next one plops into place. Even now I know what’s probably after the next one, but I can’t figure out who the characters are, I just know the setting. [I think to myself,] I’m going to finish this book because I won’t know what’s next until I’m done.